Recommendation 7: Check the age of the child and parental consent while respecting the child's privacy

09 August 2021

Checking a child's age and parental permission is a complex but crucial issue: how can we protect children if we cannot identify them or know who has parental authority? How can this be achieved without undermining the principle of online anonymity?

I enter fake information because of my parents.

44%

of 11-18 year olds say they have lied about their age on social networks

(Source - in French: Génération numérique survey "Digital practices of young people aged 11 to 18", March 2021)

Unfortunately no "magic solution" just yet

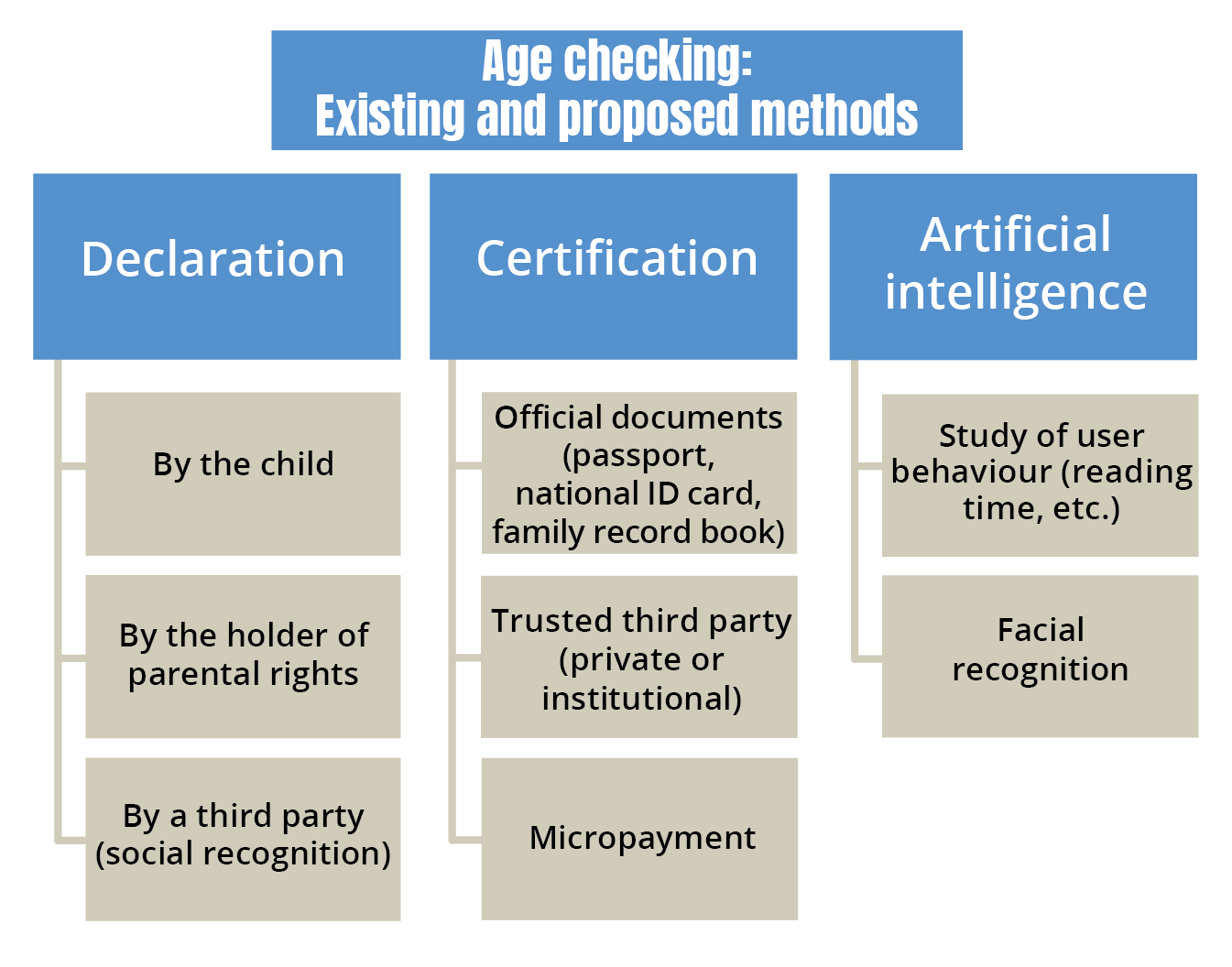

When it comes to checking age, a CNIL benchmarking study found that existing or proposed systems are generally unsatisfactory on two counts. Some are based on the mass collection of personal data and therefore appear dubiously compliant with data protection principles (e.g. facial recognition). Others are less intrusive but ineffective because they are too easily circumvented by children (e.g. self-declaration or email verification).

As regards checking parental authorisation, we must remember that in principle, this must come from both parents irrespective of their relationship status (marriage, civil partnerships, cohabitation, etc.) and whether they live together or separately. However, it may be given by just one parent, for example if the courts feel it is in the child's best interests when separated parents are unable to agree. How then to identify which parent is authorised to give consent without asking for intrusive information?

In response to these findings and concerns, the European Commission launched a call for tenders to study the feasibility and reliability of an interoperable technical infrastructure dedicated to the implementation of child protection mechanisms, such as age verification and parental consent. The technical measures should in particular be based on the electronic identification (eID) means that are being developed in various EU states. The project should also result in a map of existing age verification and parental consent mechanisms, identifying the most appropriate practices.

What the law says

The legal framework was laid down by the EDPB in its guidelines on consent of 28 November 2017, revised in 2018.

It pointed out that by setting an age limit above which children can, in certain cases, validly consent to the processing of their own data, Article 8.2 GDPR implicitly establishes the need to verify age. These Guidelines explain that, in strict GDPR terms, online service providers have an obligation of means to check age and parental consent and must make "reasonable efforts" to do so, "taking into account the technologies available".

They also stress the need for proportionality, based on an assessment of the risks involved, in accordance with the principle of minimisation. The compliance of the solution must be analysed in light of the available technologies, taking into account the nature of the proposed processing as well as the associated risks. This approach forms the basis of the CNIL's stance and has been widely adopted by the data protection authorities that have examined this issue. In this sense, it is worth noting that in the UK, for example, the ICO states in its code of practice for Age Appropriate Design that if an online service is low risk, a self-declaration method alone may be sufficient. It also recommends avoiding hard identifiers (passports, credit cards) unless truly warranted.

Help and Guidance from the CNIL

The CNIL believes that although systems for checking age and parental consent must be put in place for certain apps and sites, the ability to browse online freely without identifying yourself must be protected. Any age and parental consent verification systems should therefore respect the following rules:

Proportionality

When choosing an age verification system, online service providers should consider the proposed purposes of the processing, the target audiences, the data processed, the technologies available and the level of risk associated with the processing. A mechanism using facial recognition would therefore be disproportionate.

Minimisation

Any system should be designed to limit the collection of personal data to what is strictly necessary for the verification, and not retain the data once the verification has been completed. The data should not be used for other purposes, including commercial uses.

Robustness

Age verification mechanisms must be robust when they are for practices or processing that involves a risk (e.g. targeted advertising for children). For these cases the use of self-declaration methods alone should be avoided.

Simplicity

The use of simple and easy-to-use solutions that combine verification of both age and parental consent could be encouraged.

Standardisation

"Industry standards" and a certification programme could be encouraged to ensure compliance with these rules and to promote verification systems suitable for a wide range of websites and apps.

Third party intervention

Age verification systems based on the intervention of a trusted third party who can check a data subject's identity and status (attribution of parental authority) could be investigated in order to meet the requirements as described above.

The CNIL will foster and monitor all ongoing and future efforts to make such solutions available to online service providers, in particular the work initiated by the European Commission.

Discover the 8 recommendations from the CNIL

1 - Regulate the capacity of children to act online

2 - Encourage children to exercise their rights

3 - Support parents with digital education

4 - Seek parental consent for children under 15

5 - Promote parental controls that respect the child's privacy and best interests

6 - Strengthen the information and rights of children by design

7 - Check the age of the child and parental consent while respecting the child's privacy

8 - Provide specific safeguards to protect the interests of the child